Originally it was customary for a pair of knives to be given as part of a bridal trousseau. The practice of giving knives first started in the 14th century. Marriage contracts of this period record the ‘attest of knife’. This practice derived from the convention of presenting a purchaser with a knife when conveying property. Around 1600, a matching knife and fork was given in well to do circles in the Netherlands. Occasionally these were made of costly silver. A set of gold bridal cutlery, however, is highly exceptional and could only be afforded by the very richest. In the seventeenth century, gold was fifteen times more expensive than silver.

The Bicker Wedding Cutlery

Wedding Cutlery

This set of wedding cutlery was given to Anna Roeloffs on the occasion of her wedding to Jacob Bicker. The iron knife blade and the tines of the fork are partly gilded and decorated with engraved acanthus leaves. The gold handles are gently rounded and widen towards the ornately sculpted end and have correspondingly decorated beading at the top. They are decorated all over with detailed enamelled foliage and fruit motifs; among them are snails, libellules and butterflies aswell as exotic birds, a pelican feeding her young, executed in beautiful shades of blue, red, green, yellow and white. The family coats of arms of the bride and bridegroom are shown in enamel slightly above the middle. The name of the bride, Anna Roeloffs, is enamelled on the side of both handles.

The Bicker League

On 29 June 1608, Anna Roelofsdr de Vrije married Jacob Jacobsz Bicker. They lived on Oudezijdse Voorburgwal in Jacob’s parental home and had five children.

Anna (1589-1626) was the daughter of Roelof Egbertzs and Grietgen Jansdr Valckenier. Her father was one of the burgomasters of Amsterdam. Her husband, Jacob Jacobsz Bicker, the son of Jacob Pietersz Bicker and Aeff Jacobsdr de Moess, was born in 1581.

Jacob was a scion of the old and important patrician Bicker family of Amsterdam.His great-grandfather and pater familias, Pieter Gerritszn Bicker, was married to Anna Codde. He earned his living trading in grain, timber and fur, and from soap works, but it was really his grandsons and great-grandsons who made their name and fame, and amassed a fortune.

The family became engaged in more and more trading ventures. Both Jacob Jacobz’s uncles, Laurens and Gerrit Bicker undertook trade expeditions to South America at their own risk and expense. In 1597 they established the Guinea Company. When the Dutch East India Company—VOC was founded in 1602, Gerrit sold his brewery and participated in the company for the then massive sum of 21,000 guilders.

The Bickers also played a role in the foundation of the Dutch West India Company, concentrated on the fur trade in Moscow, and had interests in shipbuilding and peat cutting. Through shrewd strategic marriages, including an alliance with the De Graeff family, who likewise belonged to the Amsterdam elite, they not only strengthened their financial position, but were also able to divide up important positions of power in the city among themselves. At its peak, in the mid-seventeenth century, seven Bickers held important political posts. The Republican family also had ties at national level: for instance, Grand Pensionary Johan de Witt was married to a Bicker. The family was known by friend and foe alike as the ‘Bicker league’. For decades they ruled Amsterdam as the city’s most powerful family and played an important role in the politics of the young Republic. Jacob Jacobsz’s career progressed as might be expected for someone of his standing: he was a merchant, a member of the dike board of Nieuwer-Amstel, a governor of Sint-Pieters hostel and a captain in the militia. Anna and Jacob died within six days of one another in 1626, probably of the plague, which was rife in the city that year. On his death, Jacob was among the wealthiest men in the city, he left a substantial estate estimated at 375,000 guilders.

Seventeenth-Century Gold and Enamel

In the seventeenth century, the incredibly expensive gold was often used in combination with other exotic and hence costly materials, such as coral, mother-of-pearl and tortoiseshell. Gold was also decorated with enamel, as we can see here. Enamelling began by putting a transparent or opaque basis on the metal ground. The different colours of enamel in powder form, made from finely ground glass, were then applied with a small brush or steel pins. This technique was very refined and consequently very popular.

For this cutlery set, the goldsmith first pierced the decoration into the gold, and then applied the enamel in bas-taille. Seventeenth-century gold enamelled pieces are now extremely rare. Few objects have withstood the ravages of time, although it emerges from archival records that gold enamelled objects were widely made from 1630 onwards. At that time, enamelled gold objects were by no means always marked in order to avoid damaging the enamel. According to guild rules, only large gold objects had to be marked in the seventeenth century. It is therefore difficult to attribute surviving pieces to a specific goldsmith, engraver or enameller.

The Waddeston Bequest

There are, however, two virtually identical sets of gold bridal cutlery and a toothpick holder with the same decorative pattern as that on this gold bridal cutlery set. They are part of the Waddeston Bequest, now in the British Museum in London. It is highly likely that all these objects were produced by the same maker or the same workshop.

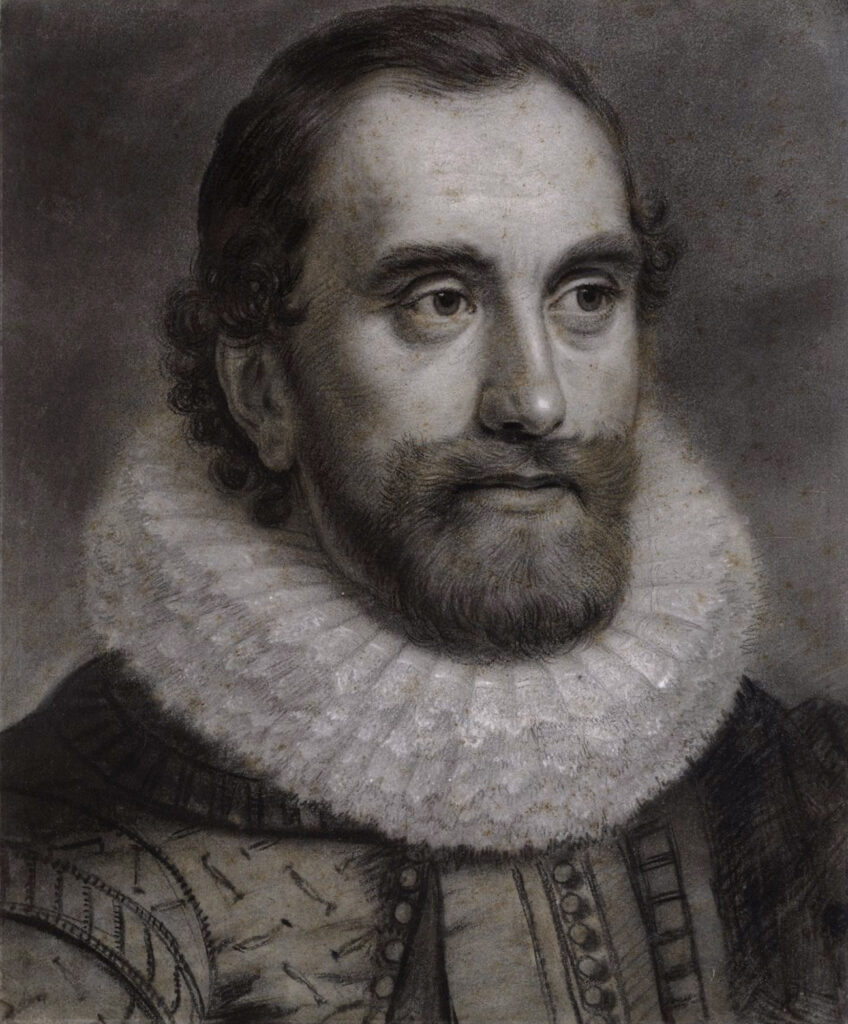

Michel Le Blon

The decoration on this set and the figures chosen strongly resemble the designs Michel Le Blon published in his books. It is highly likely that he designed and he or his workshop made this bridal cutlery set. Michel Le Blon, also written as Michel Le Blond or Michiel Blondus, was born in 1587 in the German city of Frankfurt am Main, the son of Christoffel Le Blon of Valenciennes and Ursula Sandrart, immigrants from the Southern Netherlands. Michel Le Blon is known as a goldsmith, engraver, art dealer and diplomat, but there are no known signed gold pieces by him. He trained in the workshop of the renowned brothers Theodoor and Johann de Bry, publishers and engravers. The earliest known engraving by Le Blon dates from 1605. We do not know exactly when he went to Amsterdam. It is generally accepted that he settled in the city around 1610, since he published his first Dutch pamphlet and his first designs that year. It could well have been earlier, though, given the dating of this cutlery to 1608.

The Rothschild Collection

Originally made for the wealthiest Amsterdam patrician family in the seventeenth century, in the nineteenth century the set found its way to the Rothschild family, one of the richest in the world. The Rothschilds, an international banking dynasty, are known for their extensive art collections. It was Mayer Alphonse James de Rothschild who managed to acquire this gold marriage set for his collection in the nineteenth century. Mayer Alphonse James, the son of James Mayer de Rothschild and Betty Rothschild, was born in Paris in 1827. Like his father, Alphonse was a banker and investor. He was a great fan of horse racing, persuaded his father to invest in a vineyard, the famous Château Lafite, and collected art en masse, with the emphasis on Dutch seventeenth-century painting and Islamic art. After his death in 1905 the bridal cutlery remained in the family by descent until recently. The similar pieces gifted to the British Museum in 1898 through the Waddeston bequest came from the collection of Ferdinand de Rothschild, Alphonse’s great-nephew.

Provenance

Jacob Jacobsz Bicker (1581-1626) and his wife Anna Roelofs de Vrij (c.1589 - 1626)

Baron Mayer Alphonse James de Rothschild (1827), in Entresol, hôtel de Saint- Florentin, Paris

Baron Édouard Alphonse James de Rothschild (1868-1949), in Fumoir sur la cour, hôtel de Saint-Florentin, Paris.

Confiscated by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg after the occupation of France in May 1940 (ERR no. R 2506).

Recovered by way of the Monuments Fine Arts and Archives Section from the Altaussee salt mines, Austria (no. 1170) and taken to the Central Collection Point in Munich on 28 June 1945 (MCCP no. 1371/87 and 1371/88).

Restituted to the Rothschild family in France on 11 July 1946 and remained in the family by descent.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.